LBMA Gold Bar Refiners ‘Must Use’ ASM Mine Output

Call to action’ at LBMA’s 2019 conference…

LBMA GOLD BAR refiners should work to develop and accept metal from so-called “informal” or ASM mining projects in frontier and emerging markets.

That was the message from last week’s Responsible Sourcing workshop – a “call to action” for the world’s leading gold bar manufacturers – held by the London Bullion Market Association on the second day of its 2019 conference in Shenzhen, China.

To be accepted by vault managers in London – storage hub for the world’s physical bullion trade – a gold bar must come from one of the refineries accredited by the LBMA as meeting its “good delivery” standards.

Rules on the fineness, shape and markings of each gold bar London will accept have been developed since the mid-18th Century. In 1993 the LBMA took over managing the list of London Good Delivery refiners (LGD) from the Bank of England. It has added financial checks to ensure each refinery’s good standing, plus – since 2012 – ever-more due diligence rules on confirming the legality and ethical standards of supplies.

These rules work to combat money-laundering, human rights abuses, and terrorist or conflict financing in the bullion supply chain. That helps the industry and its customers meet laws such as Dodd-Frank in the US and the UK’s Modern Slavery Act, as well as the OECD’s responsible sourcing guidance.

But like the LBMA’s new rules on environmental, social and governance issues (ESG) – now added by its 2019 Responsible Sourcing update – these requirements also work to stop approved refiners accepting material from artisanal and small-scale mines (ASM).

“After Dodd-Frank was passed [in 2010],” says ‘impact investor’ Matthew Chambers, writing in the LBMA’s Alchemist magazine this summer, “many industry schemes, responding to section 1502 [and its block on ‘conflict minerals’ from the Congo], failed to value the existing systems and technical competencies and capacities of the ASM community,” leading to a blanket refusal to accept metal from the region.

Such caution reflects the “huge reputational risk for our industry” which handling informal supplies can present, noted Tom Kendall of Chinese-owned bullion bank ICBC Standard in his LBMA 2019 summary at the close of last week’s conference.

Swiss refiners Metalor, for instance, have been working with the government of Peru since 2014 to help “formalize” its gold mining sector, but its local supplier had 91 kilograms of gold seized by Peruvian customs on route to Switzerland, accused of acting “to collect gold of illicit origin, legitimizing it using the name of a company authorized by the state” in a case still ongoing in late 2019.

Besides leaving ASM workers to seek a price from often criminal players, rejecting all ASM output as too risky also creates a problem for the accredited refining industry, because – already facing huge overcapacity worldwide – it’s missing out on a growing source of gold-mine output as the supply from large, stockmarket-listed players starts to turn lower.

Speakers at last week’s LBMA event agreed that helping informal mine operations prove their legality, ethics and ESG standards can be very costly for a refiner. The sanction for accepting illegal metal – knowingly or not – is greater still, costing an approved refiner its LBMA accreditation, destroying its sales, and also risking criminal prosecution.

The LBMA’s challenge to LGD refiners? “We need to be getting ASM gold into London Good Delivery refineries,” said Neil Harby, formerly head of evaluation at the Rand Refinery in South Africa and now the LBMA’s chief technical officer.

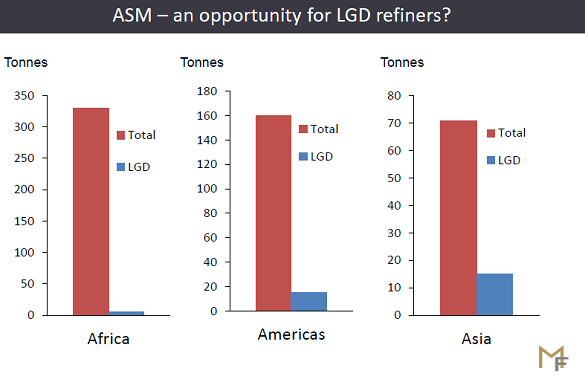

Only 5 gold-bar refineries on the LGD list currently take in any ASM doré (the pre-processed ore usually received for refining), said Harby. Yet ASM now accounts for around 30% of the global mine output available to the international refining market, added Philip Newman of independent consultancy Metals Focus, estimating that – while “unknowable” by definition – ASM supplies now total some 560 tonnes per year.

Alongside the lack of formal documentation, “There’s no balance-sheet or reserves’ estimate for a refiner to review,” explained Metals Focus’ Newman at this month’s LBMA event. ASM supplies also tend to be volatile over the short-term.

But leaving this metal to the informal market and, ultimately, non-LGD refiners only worsens the supply shortage hitting the accredited industry.

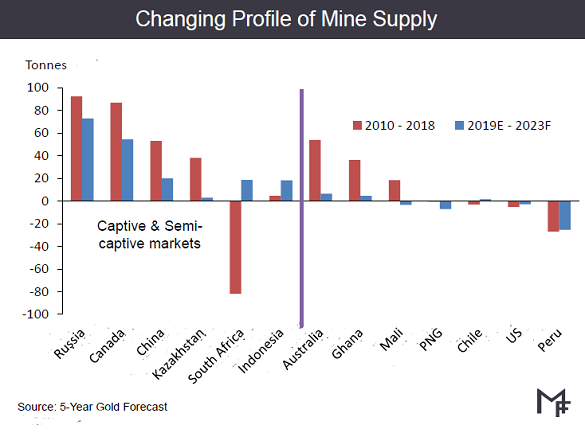

Supplies from “open” gold mining nations have flat-lined or fallen this decade, Newman went on. This contrasts with growth among “captive” or “semi-captive” markets where – because of local law, international sanctions, long-standing convention or the ownership of nearby facilities by gold producers themselves – new doré is processed by domestic refineries, rather than seeking the best-value treatment internationally.

Output from 5 of the top 10 gold-mining nations is closed in this way, leaving the Swiss, US and Australian refining industries with a shrinking pool of potential feedstock.

No.1 gold miner China bans all exports of ore (as well as of refined bullion). Most provinces in No.5 Canada require first-stage processing of any mineral ore is done domestically. The Rand Refinery in former world No.1 South Africa (now in 9th position) is owned by 5 of the country’s largest gold-mining companies.

That secures a steady flow of material for Rand – the world’s largest gold refinery when it first opened in 1921 – but it could process well over twice the 125 tonnes of bullion produced in 2018 by South Africa’s domestic mining industry. Looking to fill the gap, Rand’s world-class competence in sampling, assaying, smelting and refining “should be maintained and expanded,” said CEO Praveen Baijnath to Mining Weekly this June, “to serve the [whole] continent” of Africa, where Ghana now leads in mine output overall, pushing South Africa into second place.

Ghana’s annual gold-mine production has risen more than 38% since 2010 on Metals Focus’ data, revised in 2019 to account for ASM output. “It has had a formalised process for legally engaging in ASM since the late 1980s,” says Marie-Noelle Nwokolo, research fellow at the Brenthurst Foundation in Johannesburg, writing at the London School of Economics. “[But] a profound lack of robust regulatory mechanisms has led to an estimated 85% of small-scale miners in the country operating on an illegal basis.”

Other west and central African nations, as well as South America and south-east Asia, have seen artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) boom this decade, thanks to rising world gold prices, growing populations, a lack of other economic opportunities, and the reach of mobile phones – now used for pricing, agreeing deals and receiving payment through transfer services such as M-Pesa.

While ASM may involve long-term projects, it typically sees occasional work supplement other sources of income such as subsistence farming. Often digging for alluvial deposits in river beds, it relies on manual labour using simple tools, rather than explosives or heavy equipment.

Unlike formal large-scale projects, notes the listed mining-industry’s World Gold Council, ASM sites usually operate outside all legal or regulatory control, without permits or inspections for health, safety, social and environmental issues. Violence, slavery and sex trafficking are commonplace in some regions, as is the use of toxic mercury – handled with no protection – to extract gold from rock.

“Workers take part on an individual basis, in family groups, in partnership, as part of cooperatives or other enterprises,” explained Metals Focus’ Newman at this month’s LBMA event. More than 40 million people work on ASM sites worldwide according to the International Institute for Sustainable Development. “About 50% of the total work on gold extraction, contributing to 90% of total employment in gold mining.”

Child labour is common. One estimate for the Democratic Republic of Congo – where the eastern DRC alone may host some 1,700 ASM sites, ranging in work-force from fewer than 10 miners to several thousand and generating perhaps $437m per year for the local economy – says children constitute 30-35% of ASM gold labourers.

“75% of gold mined in the Philippines comes from small-scale miners,” said Maria Santiago, senior assistant governor at the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, speaking at the start of LBMA 2019’s second day in Shenzhen last week.

Now the third largest gold mining nation in Asia – and with today’s only central bank to run a London Good Delivery refinery – the Philippines first recognized the importance of ASM in 1991, Santiago explained, passing the People’s Small-Scale Mining Act and ordering the central bank to buy “all gold produced by small-scale miners in any mineral area…at prices competitive with those prevailing in the world market regardless of volume or weight.”

Further legislation supporting ASM gold mining came in 1995, but in mid-2011 – when global gold prices were then setting all-time record highs – the Philippines government imposed a tax on gold sold to the central bank. That spurred a 99% collapse in annual sales of domestically-mined gold to the Bangko Sentral by last year, driving ASM supplies into “informal hands” for export overseas, rather than helping boost the nation’s bullion reserves.

The tax was repealed earlier in 2019 after the central bank successfully argued that “Gold purchases from small-scale miners benefit the BSP and the country.” Mining offers a subsistence income to three-quarters of the Philippines’ 500,000 ASM workers, helping support perhaps 2.3 million Filipinos. For the central bank, Santiago said, “Buying gold using Pesos increases the country’s gross international reserves, whereas buying gold using US Dollars only alters the composition but does not increase it.”

For the global gold-refining sector, estimates quoted by the Financial Times in 2004 – when Johnson Matthey closed its last gold processing plant in the UK, losing 250 tonnes per year of capacity – said the industry could process some 12,000 tonnes of bullion per year, then about 3.5 times the size of annual world gold mine output.

Such “chronic overcapacity” meant “poor returns for refinery owners.”

Overcapacity has since fallen to perhaps 2.5 times annual mine output, but gross profit margins on toll refining – where a mining company delivers doré and pays a per ounce fee to receive large wholesale-market bars of bullion – have fallen to just 20 cents according to 2018 comments from major refiners at that year’s LBMA conference, driven down in part by “the proliferation of new gold refineries, all seeking doré feed,” according to Metals Focus’ Gold Focus 2019 report.

“Many are not LBMA-registered and are therefore not necessarily [or] always constrained by responsible sourcing rules.”

One major London Good Delivery contract, reportedly won in 2019 from 15-year incumbent Valcambi by Swiss rivals Argor-Heraeus and Pamp plus Japanese-owned Asahi in the US, could be worth as little as 5 cents per ounce according to Reuters, down 95% from standard terms at the start of the 2000s.

Looking at the scope for accredited refiners to help legalize and accept ASM flows, “We have done independent work on this before,” says analyst Rhona O’Connell – now at brokerage INTL FC Stone – “and the onus on the refiners in terms of costs and logistics is already heavy.”

“While compliance costs are rising for the refining industry,” says Newman from Metals Focus, “the potential value of ASM feedstock is not.”

But global growth in gold-mine output is slowing, Newman stressed, meaning that ASM offers “a tremendous opportunity” for accredited refiners.

“The inference from [the LBMS’s Shenzhen] workshop and the conference as a whole,” says O’Connell, “is that the Association stands ready to take it on.”

Source: Bullion Vault