Officials quash plan, for now, to develop Philippines’ biggest copper mine

By Bong Sarmiento

- The Philippine municipality of Tampakan has canceled an agreement with Sagittarius Mines, Inc. to develop a $5.9 billion copper and gold mine on the island of Mindanao.

- Municipal councilors criticized the “lopsided” nature of the deal that they said had not been periodically reviewed as required and had sold the community short.

- The Tampakan project has faced opposition since mineral reserves were discovered there in the ’90s, with pushback coming from various levels of government, Indigenous communities, the Catholic church, environmentalists, and even communist rebels.

- An Indigenous group that has taken up arms against the project has warned of more bloodshed should the project go ahead on their ancestral lands.

SOUTH COTABATO, Philippines — Officials in the southern Philippines have canceled a $5.9 billion project to exploit Southeast Asia’s largest known undeveloped copper and gold reserves, but have left open the possibility of the venture being revived.

The municipal council of Tampakan, home to 40,000 people in the province of South Cotabato, alleges that Sagittarius Mines, Inc. (SMI) failed to honor its side of the agreement governing the development of the mine. That deal, the municipal principal agreement (MPA), is supposed to be reviewed and updated every four years, but this hasn’t been done since 2009. There were attempts to review the MPA, but the mayor and other municipal representatives were excluded from the negotiations, the council said.

“After scrutiny, there are provisions in the MPA that are considered vague, disadvantageous to inhabitants of Tampakan and unduly tie the hands of the local government unit [LGU] of Tampakan,” the council said in a resolution dated August 10 but made public on August 14. “As such, the LGU cannot sit and fold its arms not to intervene in any action initiated by its people if, indeed, their rights have been violated contrary to some provisions of the agreement.”

The MPA was already a done deal rather than being negotiated with the government, the resolution said.

Site of the SMI’s Tampakan mining operation in Mindanao. Image courtesy of SMI

Municipal legislators say they’re no longer interested in reviewing or updating the 2009 MPA with the company but are open to creating or formulating a new agreement, which means SMI could still pursue the mammoth Tampakan project under a new municipal agreement.

The resolution has been sent to relevant government agencies but SMI has yet to issue a statement as of the time this article was published. Mongabay sought comment from SMI officials but did not receive a response from the mining firm.

‘Lopsided,’ ‘no justice’

If approved, the Tampakan project would be the largest copper mine in the Philippines and among the largest in the world. The site is predicted to yield an average of 375,000 tons of copper and 360,000 ounces of gold in concentrate per year over a 17-year period. In 1995, the Philippine government granted the Tampakan project the contract to explore and develop the area’s mineral deposits through a financial or technical assistance agreement (FTAA).

The MPA took effect in 1997, and since then SMI has paid Tampakan municipality at least 40 million pesos ($822,370 at current rates), or an average of 2.5 million pesos ($51,400) a year as part of its financial commitments, according to a 2013 state audit. But the terms of the deal are “lopsided,” the council noted in its recent decision

Days before the council published its resolution, Tampakan Mayor Leonard Escobillo criticized the rental rate that SMI was set to pay for the ancestral lands of the Blaan, the ethnic tribal group whose mountain home will be affected by the project.

Road repairs funded by Sagittarius Mines, Inc benefit Sitio Kampo Sinko, Barangay Danlag in Tampakan, South Cotabato as seen in this photo taken on January 16, 2020. Image by Bong S. Sarmiento

Escobillo said the mining firm was set to rent the Indigenous lands for 160,000 pesos (around $3,300) per hectare for 25 years, which works out to 6,400 pesos ($131) a year or 533.33 pesos ($11) a month.

Escobillo, who succeeded his father, Leonardo, a staunch supporter of mining during his three terms as the town’s mayor, said the land rental rate was part of the negotiations for obtaining the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of the affected community — one of the major requirements for the company to proceed with the project, along with local government endorsements.

“I believe there’s no justice in that [price],” Escobillo said on Aug. 12. “You rent one hectare of land and you’ll use it for 25 years, that’s only 500 pesos a month. How will a family live with such [an amount]?”

Alyansa Tigil Mina (ATM), a national advocacy group whose name translates as Alliance Against Mining, lauded the Tampakan municipal council for terminating the deal with SMI. It also urged President Rodrigo Duterte, who vocally banned open-pit mining in 2017, to order an executive review of the Tampakan contract.

“[Tampakan officials] have exercised the spirit and substance of local autonomy in ensuring the general welfare as well as ensuring a safe and sound environment of their constituents,” Jaybee Garganera of ATM said in a statement. “The people of Tampakan and the Blaan Indigenous communities affected deserve to be heard in their rejection of this massive and potentially destructive mining project.”

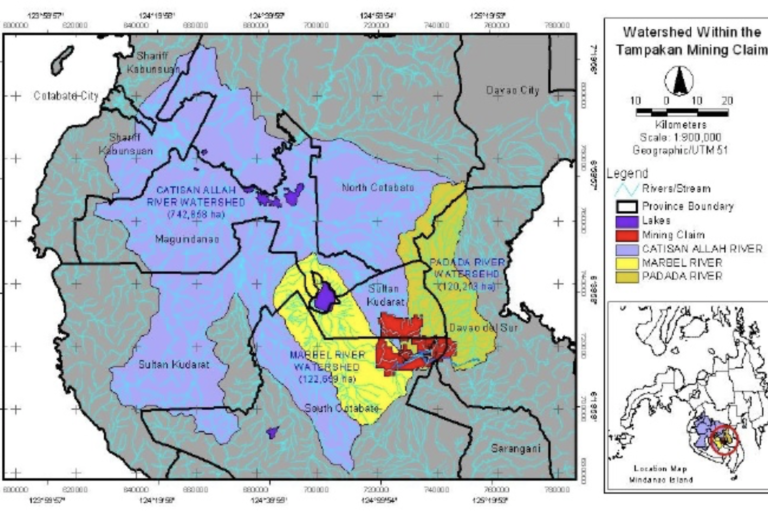

Map of Tampakan’s mining claim and the watersheds. Image courtesy of CCCP

Pushback from clergy and communists

Nestled some 1,300 meters above sea level, the proposed mining site remains untapped in the mountains of Tampakan more than three decades after the discovery of copper and gold reserves there.

Its ownership has changed hands several times. Australian firm Western Mining Corp. (WMC) made the original discovery in 1994, before selling the mining rights to SMI. The national government approved the transfer of the FTAA from WMC to SMI in 2001. Exploration activity resumed in 2002 with investments from Indophil Resources NL, also an Australian company, and the Mindanao-based conglomerate Alsons (Alcantara and Sons) Group.

Multinational miners Xstrata Copper and Glencore Plc. later became SMI shareholders; Glencore would go on to acquire Xstrata in 2013. In 2015, Alsons Group gained control of the Tampakan project after Glencore pulled out, and by December 2017, SMI’s company structure is “100 percent Filipino,” according to the Philippine government’s Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB).

The cancellation of the municipal agreement is the latest setback for the Tampakan project, already blocked by a ban on open-pit mining imposed by the South Cotabato provincial government since 2010.

SMI and its supporters have challenged the legality of the ban, saying the extraction method doesn’t violate national mining laws. A local court has yet to render a decision in the case.

The project faced trouble even before the ban came into force a decade ago. These include security threats from communist rebels and opposition from the local Catholic church, environmentalists and some members of the Blaan tribe.

On New Year’s Day in 2008, communist rebels stormed and burned the SMI base camp in the village of Tablu in Tampakan municipality. The rebels fled with several firearms taken from company guards. The church, meanwhile, has long rejected the mining project, citing its potential environmental hazards as well as concerns over food security and the human rights of the Indigenous peoples in the affected area.

In 2017, the late former environment secretary, Gina Lopez, canceled the Tampakan project’s environmental compliance certificate (ECC) “due to environmental and social concerns.” But in July 2020, the MGB regional office revealed that Duterte’s office had restored the ECC, a decision that was in effect as early as May 6, 2019.

In a similar move, the firm’s 25-year FTAA, which was set to expire on March 21, 2020, was extended for another 12 years in an order that was dated June 8, 2016, but only made public in January 2020. The 12-year extension will allow SMI to operate the mine until 2032, with the possibility of a renewal through 2057.

Gearing up for extraction

Prior to the termination of the municipal agreement, the firm had been gearing up for the commercial production phase. In the past two years, SMI has spent at least 103 million pesos ($2.1 million) on repairing 17.4 kilometers (10.8 miles) of roads in at least two villages in the area, according to the 2019 company report.

The company calls itself a “responsible miner,” citing the commendations it received from the Presidential Mineral Industry Environmental Awards in 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013.

Local radio advertisements have been running in recent months repeating this “responsible miner” tag and touting the economic boost that the mine would have in transforming poor communities and changing thousands of lives through job creation.

The controversial Tampakan project straddles scattered communities mostly belonging to the Blaan ethnic tribe. Image by Bong S. Sarmiento

Power supply lines, a major support facility for the mining operation, have already been put in place in the mountains of Tampakan, along with canals and gabions, while exploration studies to determine the stability of the ground for other support facilities are still underway.

On a slope near the SMI base camp in Tablu village, workers were seen in January putting in place soil erosion blankets made from coconut husks.

Escobillo said that month that SMI targets to start mining operations in three years if it can acquire the needed permits from the relevant government agencies, including the ECC from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and FPIC from the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

Indigenous opposition and bloodshed

While some Indigenous leaders support the project, others oppose it. Blaan tribal leader Daguel Capion, who used to lead an armed group against the project and has admitted to killing at least three construction workers on the site in 2011, warned of chaos and more bloodshed should SMI proceed with excavating the vast mineral deposits.

In 2013, SMI scaled down its operations, retrenching about 1,000 workers as part of a revised work plan that sought, among other things, to get approval from various government levels and agencies to move the project to the commercial production stage.

“In the years leading to and during the exploration phase, the company would approach and consult with us,” Capion told Mongabay in January. “But nowadays, there are no more negotiations; the community is being kept blind. I hope the company will be more transparent to us.”

Daguel Capion speaks to this journalist in 2012 within the Tampakan mines development site. Image by Bong S. Sarmiento

At least six of Capion’s immediate family members and relatives, including his wife, Juvy, and their two children, were killed in separate instances within the Tampakan project area. Juvy and the children were killed in October 2012 during a military operation aimed at arresting Capion, who was then facing murder charges for the deaths of three people working for a road project funded by SMI the year before.

Capion, who used to work as a community relations officer for SMI before taking up arms in opposition to the Tampakan project, was subsequently arrested in 2015 in neighboring Sarangani province but released almost a year later due to insufficient evidence.

Before his arrest, he had admitted to killing the construction workers and had been linked to several other alleged murder and attempted murder cases targeting government troops and company guards in the mine development site.

Capion, who is highly regarded by his clan and for years has been recognized by environmentalists and the local Catholic church as a legitimate community leader until his group’s disgruntlement turned violent, warned that “more lives will be lost if the large mining project will be allowed to proceed” on the Blaan ancestral land.

Source: Mongabay